|

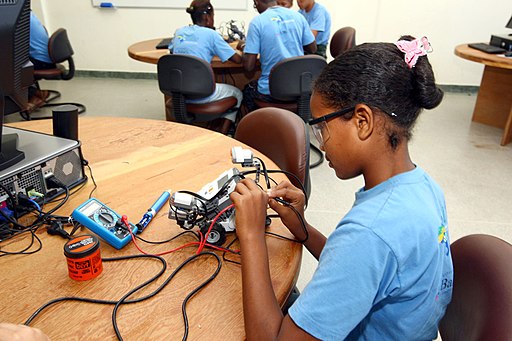

| By Agecom Bahia [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

Atheists in the U.S. are fond of pointing the finger at evangelical fundamentalist Christianity. I think we are right to do so. Much of the hostility toward science originates from those who fear "evilution" and are confused by the existence of monkeys. At the same time, this is only one of the factors driving these attitudes. Even if we somehow managed to stamp out this toxic form of Christianity in the next decade or two, I think we'd still have negative attitudes toward science.

Another factor besides fundamentalist Christianity that doesn't get enough attention is the quality of the science education to which children are exposed. It seems to me that this is sometimes even more important than religion in shaping attitudes toward science. If a child learns that science is difficult, boring, and/or irrelevant, he or she may give up on it prematurely. That may be okay since science does not have to be something everyone is interested in pursuing; however, I suspect that some early negative experiences with science education may lead people to develop some of the anti-science attitudes that can cause problems for all of us later on.

My earliest exposure to science in school came in the 4th grade, and I don't think my teacher could have done a better job with it than he did. He made science exciting, and we were all hooked. Unfortunately, my middle school science teacher, who was sometimes drunk during class, turned many of us off to science by making it about as dry and boring as could be. My high school science experience was a mixed bag. I had an outstanding teacher in anatomy & physiology and a terrible one for chemistry. By this point, it was already too late for many of my peers. Despite many having an early interest in science, all it took was one bad class in middle school for them to conclude that it wasn't for them.

Having another bad class in high school served to strengthen the views of science as boring, too hard, irrelevant, and even pointless. I remember many of us in that high school chemistry class, including me, saying things like, "If this is science, it isn't for me." Since some of us had been looking forward to the class, that was a shame. Others had even less positive reactions. For them, science had become "stupid" and something we didn't really need.

I think it is helpful to remember that many children find science difficult even if they like it. For some, the fact that it is perceived as difficult may be enough to turn them off. Others will stick with it and work harder to understand it if it continues to be interesting and relevant. But if it is hard and the teacher is awful, sticking with it becomes less and less likely. And if these early experiences are bad enough, children may grow up to be adults who are not merely uninterested in science but actually hostile to it. And so, I think that working to improve the quality of science education is probably one of the best things we can do to prevent the sort of negative attitudes toward science that limit our progress.

For information on what you can do to improve the quality of science education in the U.S., check out the National Center for Science Education (NCSE).